Arts and creativity for fulfillment

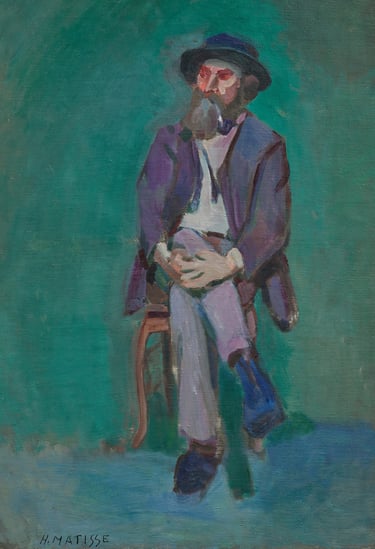

Matisse’s seated man

Matisse’s seated man in the light of Musarthis resilience, color, and the complexity of art. A rereading of Matisse’s portrait through the lens of resilience, between color, silence, and restrained intensity.

Musarthis Team

8/20/20254 min read

Matisse’s seated man in the light of Musarthis: resilience, color, and the complexity of art

At Musarthis, we believe that resilience is woven through poetry, contemplation, and creativity. For us, art is a refuge—an inner space of transformation where wounds may find in beauty a path toward healing. It is in this spirit that we revisit Matisse’s Seated Man, an emblematic work from the turn of the 20th century, as an ode to resilience expressed through color and simplicity. Yet we also acknowledge that not every artwork lends itself to a soothing interpretation: the richness of art lies precisely in its ability to unsettle, to question, and to open unexpected horizons.

Color: vital energy and affirmation

In Seated Man, Matisse liberates color from academic constraints. Vibrant tones, bold flat areas, and assertive contours do not seek resemblance but rather the expression of an inner force. This approach resonates with our philosophy: here, color becomes a balm, an energy that both soothes and awakens. It invites us to feel, to immerse ourselves in the presence of the model, to let light filter through the shadows of existence.

But in the context of the time, this choice of color was also an act of rupture—a deliberate rejection of academicism and a claim for artistic freedom. Matisse’s color is not merely calming: it is affirmation, power, sometimes even disorienting for viewers accustomed to other aesthetic codes. This subversive and innovative dimension is integral to the strength of the work.

Silent resilience and transformation: one possible reading

Like the creative rituals we often propose, this portrait may be read as the testimony of a discreet yet powerful resilience. The man, seated, frontal, seems to traverse life’s turmoil with profound serenity. Matisse himself, then in search of renewal, turned painting into a gentle act of resistance: transforming trial into beauty, doubt into creative energy. This posture—both simple and grounded—embodies the human capacity to absorb shocks, to reinvent oneself, to be reborn through art.

Still, we must acknowledge that this is a contemporary interpretive choice, shaped by our own values of resilience and well-being. There is no evidence that Matisse intended this portrait as a manifesto of resilience: it may also be viewed as a formal experiment, a stylistic exercise, or even as a quiet interrogation of solitude, gravity, or the human condition. What soothes some may unsettle others: the experience of art is profoundly subjective.

Art as a Space of healing… and of disturbance

We celebrate art as a path of healing, a “cerebral sedative” in Matisse’s own words. Seated Man thus becomes more than a portrait: it is an invitation to contemplation, to pause, to reconnect with oneself. Color, light, the simplicity of the pictorial gesture open a space where burdens may be set down, where balance may be restored, and where beauty provides the strength to continue.

Yet it would be reductive to limit art to this sole soothing function. Art, including that of Matisse, can also provoke, disturb, and question. Seated Man is not necessarily a refuge: it may evoke unease, strangeness, or a deeper reflection on the human condition. The ambiguity of art—its power to stir contradictory emotions—deserves to be fully embraced. It is in this ambivalence, this dual potential to be both balm and enigma, that the richness of the work resides.

The Musarthis perspective

At Musarthis, we resist reducing an artwork to a single function or reading. We welcome its complexity, its ambivalence, and the diversity of experiences it awakens in each of us. For us, the strength of art lies precisely in this openness: it may soothe, but also unsettle; console, but also provoke. Every gaze upon a work is singular; every interpretation, however inspiring, remains subjective and partial. It is within this richness, in the refusal of art to be reduced, in its ability to open multiple—even contradictory—spaces of meaning, that we draw our inspiration and our wonder.

Thus, Matisse’s Seated Man, revisited in the light of Musarthis, embodies this fertile tension: it is at once a promise of resilience and an invitation to explore the complexity of human experience—in all its beauty, paradoxes, and mysteries.

Sources

Christie’s. “Homme assis,” lot notes and essay, 2025. (Historical and stylistic analysis, Cézanne’s influence on Matisse, context of creation and the evolution toward Fauvism.)

Christie’s. Collecting guide: the life and art of Henri Matisse. (Overview of Matisse’s career, his relationship to color, the model, and modernity.)

Centre Pompidou. “Homme assis et tête d’homme,” artwork entry and analysis. (Technical description, 1899–1900 context, Cézanne’s influence and the evolution of Matisse’s drawing.)

Muzeo. Reproductions of Fauvist paintings. (Origins of Fauvism, Matisse’s role, the importance of color and formal simplification.)

Tavel & Simon. Henri Matisse: valuation, prices, and estimates in 2025. (Stylistic features, recurring motifs, and Matisse’s techniques.)

About the Artist

Henri Matisse (1869–1954) is one of the leading figures of modern art. A French painter, draftsman, printmaker, and sculptor, he emerged as the leader of Fauvism, the movement that revolutionized the use of color at the beginning of the 20th century. Matisse constantly explored new paths, breaking away from classical representation to express an inner vision of the world—radiant and free. Marked by life’s trials, he transformed constraint into creative strength, continuing his work even through illness, notably with the invention of his celebrated paper cut-outs. His art, both simple and profound, remains an ode to vitality, beauty, and human resilience.

Seated Man, c. 1900

Oil on canvas – 65 × 45 cm

Private collection | Public domain

MUSARTHIS

La Chaux-de-Fonds

CH-2300

Contact

info@musarthis.world

All rights reserved musarthis.world

Made in Switzerland